“Some of the time, going home, I go

Blind and can’t find it.”

– Looking for the Buckhead Boys

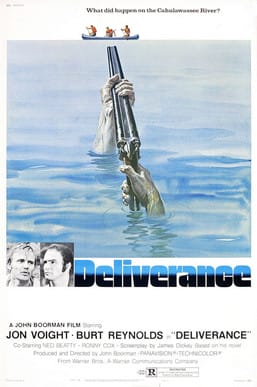

Born in 1923 to parents Eugene Dickey and Maibelle Swift, James Lafeyette Dickey grew up in Buckhead and made his ties to the community quite clear throughout his life. Dickey was a poet, novelist, critic, lecturer, and one of the original Buckhead Boys. Though by all accounts he was about as far from an elitist as one could get, his writings included the famous poem Looking for the Buckhead Boys, a book called Deliverance which was later turned into a film by the same name, and in 1966 he became 18th Poet Laureate of the United States.

Dickey considered his style of poetry to be “country surrealism” and the topics of his works leaned towards reminiscence of days gone by, the juxtaposition of nature and civilization, and a tender approach to the mortality of parents.

After graduating from North Atlanta High School, Dickey went on to attend Darlington School in Rome, Georgia for just one year before asking to be dismissed due to what he perceived as rampant hypocrisy, cruelty, and class privilege at the school. In 1942 Dickey enrolled at Clemson Agricultural College of South Carolina where he played tailback on the Football team. He later served in the military as a radar operator for the United States Air Force for two stints during the Second World War and Korean Wars. He first began experimenting with poetry when he was a member of the 418th Night Fighter Squadron for which he flew more than 100 combat missions.

Between his stints in the military, Dickey attended Vanderbilt University where he graduated with a degree in English and philosophy in 1949. He proceeded to teach and lecture for several years followed by generating copy for Atlanta’s own Coca-Cola Company. He was later let go from the company for shirking his responsibilities, and he established his trajectory into his passion for literary arts. He began writing seriously and fervently, and continued teaching at multiple institutions including the University of South Carolina where he worked as a professor of English and writer-in-residence for the remainder of his career.

Dickey’s fame grew when he wrote a poem for the Apollo 11 launch titled The Moon Ground for Life Magazine and read it on ABC Television in 1969, recited The Strength of Fields at Jimmy Carter’s 1977 inauguration, and was named a poetry consultant for the Library of Congress in 1967.

In Conversations with Writers, he remarked on his career shift into poetry and touched on his emotional attachment to the work. “There could have been no more unpromising enterprise or means of earning a livelihood than that of being an American poet,” said Dickey. He believed that every person had a poet inside of them yearning to get out, and he simply possessed the compulsion to allow his free reign.

Some might consider Dickey a ‘good old boy,’ whose military career and propensity for sports seemed ill-suited for a poet, but he managed to weave together these various elements of his persona into timeless, nostalgic works that earned him the highest honors. He cared more for establishing rhythm than following the rules and often experimented with syntax and form in his writing.

A common theme of Dickey’s poetry is a sense of otherness; his pieces often speak from the perspective of subjects who are reflecting upon their own lives. A sort of third person’s third person. In this way he is able to personify animals and fuse their experiences with a human’s, bringing a unique viewpoint to topics such as hunting, mortality, and nature’s conflict with modern society.

The world catches fire.

I put an unbearable light

Into breath skinned alive of its garments:

I think, beginning with laurel,

Like a beast loving

With the whole god bone of his horns:

The green of excess is upon me.

– Springer Mountain

Dickey highlighted Buckhead in his famous poem, Looking for the Buckhead Boys, in which he drops names of folks he grew up with and mentions all the places he loved when he was young like Wender & Roberts, North Fulton High School (now North Atlanta High School), Tyree’s Pool Hall, and the Gulf gas station. He reminisced about catching up with old friends, some of whom had passed, and speculated about how things had changed since his youth.

James L. Dickey died in 1997 at the age of 73 in Columbia, South Carolina. He will always be remembered for his talent and poetry, and Buckhead will always claim him as one of their own Buckhead Boys.

by James Dickey

Some of the time, going home, I go

Blind and can’t find it.

The house I lived in growing up and out

The doors of high school is torn

Down and cleared

Away for further development, but that does not stop me.

First in the heart

Of my blind spot are

The Buckhead Boys. If I can find them, even one,

I’m home. And if I can find him catch him in or around

Buckhead, I’ll never die: it’s likely my youth will walk

Inside me like a king.

First of all, going home, I must go

To Wender and Roberts’ Drug Store, for driving through I saw it

Shining renewed renewed

In chrome, but still there.

It’s one of the places the Buckhead Boys used to be, before

Beer turned teen-ager.

Tommy Nichols

Is not there. The Drug Store is full of women

Made of cosmetics. Tommy Nichols has never been

In such a place: he was the Number Two Man on the Mile

Relay Team in his day.

What day?

My day. Where was I?

Number Three, and there are some sunlit pictures

In the Book of the Dead to prove it: the 1939

North Fulton High School Annual. Go down,

Go down

To Tyree’s Pool Hall, for there was more

Concentration of the spirit

Of the Buckhead Boys

In there, than anywhere else in the world.

Do I want some shoes

To walk all over Buckhead like a king

Nobody knows? Well, I can get them at Tyree’s;

It’s a shoe store now. I could tell you where every spittoon

Ought to be standing. Charlie Gates used to say one of these days

I’m gonna get myself the reputation of being of being

The bravest man in Buckhead. I’m going in Tyree’s toilet

And pull down my pants and take a shit.

Maybe

Charlie’s the key: the man who would say that would never leave

Buckhead. Where is he? Maybe I ought to look up

Some Old Merchants. Why didn’t I think of that

Before?

Lord, Lord! Like a king!

Hardware. Hardware and Hardware Merchants

Never die, and they have everything on hand

There is to know. Somewhere in the wood screws Mr. Hamby may have

My Prodigal’s Crown on sale. He showed up

For every football game at home

Or away, in the hills of North Georgia. There he is, and as old

As ever.

Mr. Hamby, remember me?

God A’mighty! Ain’t you the one

Who fumbled the punt and lost the Russell game?

That’s right.

How’re them butter fingers?

Still butter, I say,

Still fumbling. But what about the rest of the team? What about Charlie Gates?

He the boy that got lime in his eye from the goal line

When y’all played Gainesville?

Right.

I don’t know. Seems to me I see …

See? See? What does Charlie Gates see in his eye burning

With the goal line? Does he see a middle-aged man from the Book

Of the Dead looking for him in magic shoes

From Tyree’s disappeared pool hall?

Mr. Hamby, Mr. Hamby,

Where? Where is Mont Black?

Paralyzed. Doctors can’t do nothing.

Where is Dick Shea?

Assistant sales manager

Of Kraft Cheese.

How about Punchy Henderson?

Died of a heart attack

Watching high school football

In South Carolina.

Old Punchy, the last

Of the wind sprinters, and now for no reason the first

Of the heart attacks.

Harmon Quigley?

He’s up at County Work Farm

Sixteen. Doing all right up there; be out next year.

Didn’t anybody get to be a doctor

Or lawyer?

Sure. Bobby Laster’s a chiropractor. He’s right out here

At Bolton; got a real good business.

Jack Siple?

Moved away. Gordon Hamm?

Dead

In the war.

O the Book

Of the Dead, and the dead, bright sun on the page

Where the team stands ready to go explode

In all directions with Time. Did you say you see Charlie

Gates every now and then?

Seems to me.

Where?

He may be out yonder at the Gulf Station between here and Sandy

Springs.

Let me go pull my car out

Of the parking lot in back

Of Wender and Roberts’ Do I need gas? No; let me drive around the block

Let me drive around Buckhead

A few dozen times turning turning in my foreign

Car till the town spins whirls till the chrome vanishes

From Wender and Roberts’ the spittoons are remade

From the sun itself the dead pages flutter, the hearts rise up, that lie

In the ground, and Bobby Laster’s backbreaking fingers

Pick up a cue stick Tommy Nichols and I rack the balls

And Charlie gates walks into tyree’s un-

Imaginable toilet.

I go north

Now, and I can use fifty

Cents worth of gas.

It is Gulf. I pull in, and praise the Lord, Charlie

Gates comes out. His blue shirt dazzles

Like a baton pass. He squints, he looks at me

Through the goal line. Charlie, Charlie, we have won away from

We have won at home

In the last minute. Can you see me? You say

What I say: Where in God

Almighty have you been all this time? I don’t know,

Charlie, I don’t know. But I’ve come to tell you a secret

That has to be put into code. Understand what I mean when I say

To the one man who came back alive

From the Book of the Dead to the bravest man

In Buckhead to the lime-eyed ghost

Blue-wavering in the fumes

Of good Gulf gas, “Fill ‘er up.”

With wine? Light? Heart-attack blood? The contents of Tyree’s toilets?

The beer

Of teen-age sons? No; just

“Fill ‘er up. Fill ‘er up, Charlie.”