It is no secret that Atlanta mayor Keisha Bottoms has had her sights set on an ambitious rewrite of the zoning ordinance that governs development throughout our community since taking office in 2018. However, the scope of the proposed changes that recently came to light, after a little-noticed press release, would have dramatic economic and aesthetic implications if passed.

Mayor Bottoms released a statement on December 4th announcing a set of recommendations from the Department of City Planning.

“The Atlanta City Design Housing Initiative builds on our Administration’s One Atlanta Housing Affordability Action Plan, addressing systemic racism and working to ensure affordable housing for all,” said Mayor Bottoms.

The ideas and proposals within the report represent two years of work by a team called Atlanta City Design Housing. “Our city is growing, and we can leverage that growth to be a better city that is more equitable, inclusive and accessible to live in,” said Tim Keane, the City of Atlanta’s Commissioner of City Planning. “Atlanta City Design Housing Initiative outlines ways this growth can be designed specifically for Atlanta’s landscape, distinctive physical characteristics and unique neighborhoods.”

The report from Atlanta City Design points out that since 2010 Atlanta has welcomed 85,000 new residents within the city limits, passing half a million people in 2019. The report suggests that Atlanta could more than double in size in the next few decades to 1,200,000 within the city limits and reach a total metro area population of 9 million.

“The city is going to change; …not changing is not an option; our change will involve significant growth; and if properly designed, growth can be a powerful tool for shaping the Atlanta we want to become” – The Atlanta City Design

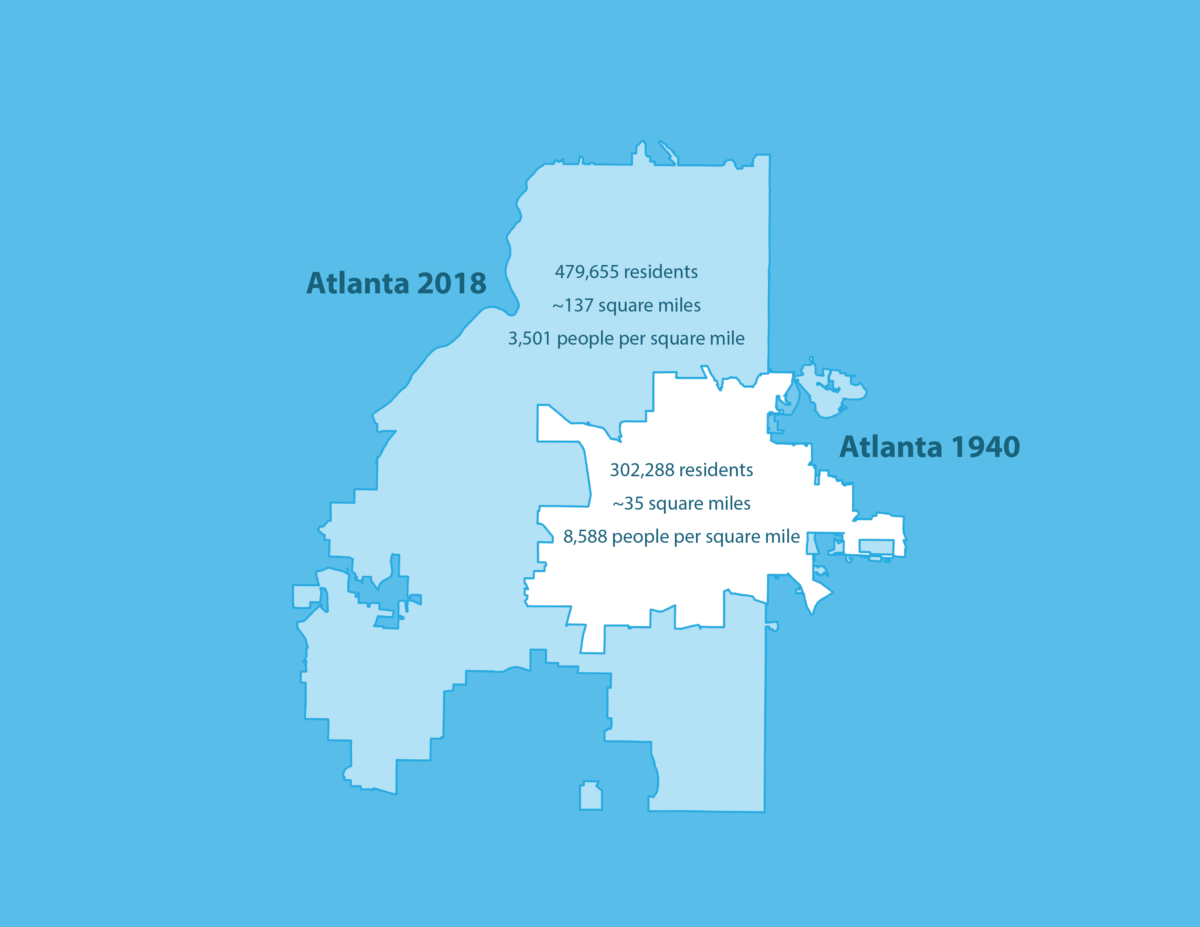

At one point, the City of Atlanta was a dense, urban place with a comprehensive streetcar system. In 1940, Atlanta was 35.2 square miles and had a total population of 302,288. Atlanta’s 1940 population density was approximately 8,588 people per square mile, nearly 2.5 times more dense than in 2018.

Atlanta in 1940 had a density comparable to that of modern-day Seattle, Baltimore, and Los Angeles. This level of density sustained over 100 miles of trolley lines and gave neighborhood commercial districts the density of residents needed to enable neighborhood economies to thrive.

What we see today as essential community planning was devised as a tool to divide races, according to the authors: “In 1922, the Atlanta City Planning Commission released a zoning plan that was explicitly racist in its zoning, stating in the plan that, ‘home neighborhoods had to be protected from inappropriate uses, including encroachment of the colored race.’ The original 1922 code had two residential zoning categories: ‘R-1 white district’ and ‘R-2 colored district.’ The Georgia Supreme Court rejected this explicitly racist language. The revised 1929 zoning code changed ‘R-1 White Districts’ to ‘Dwelling House Districts’ and ‘R-2 Colored Districts’ to ‘Apartment Houses.’ The change meant that zoning could no longer restrict areas of the city based on race.”

When I got to this, my jaw dropped. Atlanta is the city in the forest and Buckhead in particular has a tree canopy over ⅔ of our neighborhoods. What makes Buckhead so special is that it is possible to enjoy living in nature, within the city.

The report states that “Atlanta should amend the City’s zoning code to allow more housing flexibility in the existing exclusionary single-family zoning areas designed for race and class discrimination.

Today, nearly 60% of the city is still zoned exclusively for single-family zoning. Atlanta’s future depends on policies of inclusion and exclusive single-family zoning is anything but inclusive. The first step toward making Atlanta a more inclusive place to live should be to end exclusive single-family zoning by allowing an additional dwelling unit in all existing single-family zoned areas in the city.

This could be done by amending the zoning code to allow an additional dwelling unit in all of the existing single-family areas.

This single zoning amendment would unlock 60% of Atlanta’s land to contribute to the city’s growth without substantially changing the character and feel of the neighborhood.”

While the premise of “ending single-family zoning” is shocking and incendiary, the actual proposed means of ending it is slightly more subtle. Ideas include allowing basement apartments and tiny houses/accessory dwelling units that would be located behind existing homes. The report goes on to suggest that these small guest-house size homes in backyards should be available to buy and sell separately from the “main” house.

Other ideas promoted in this report include reducing minimum lot sizes, allowing small apartment buildings in some neighborhoods currently limited to single-family homes, and mandating that wealthy neighborhoods have their per-capita share of “affordable housing.” The full details may be read here.

As a real estate broker in Buckhead, I see people make choices every day about the type of neighborhoods they want to live in. Some may choose to live in a high-rise condo building along the Beltline in East Atlanta or a shotgun-style mill house in Cabbagetown. Other people would prefer several acres of their own land surrounded by other similar properties. These choices involve both the person’s preferences and what their budget allows them to afford. Diversity is what makes a city interesting and diversity of wealth is just one factor that makes us all different.

Yes, this does mean that some neighborhoods are “exclusive.” Is that a bad thing, something that should be changed?

I will assume that Mayor Bottoms, Tim Keane, and Atlanta City Design all have the best intentions. They want to increase the supply of housing to keep pace with the increasing population and help pull people out of poverty who have been disadvantaged. I think that is a great premise, but they should work to find a way to do it without driving out those with more wealth. If you take away the housing choices that a wealthy individual is looking for then they will go elsewhere to find it, and take their tax money with them. That does not contribute to a healthy and diverse city.

It is unclear how or when Mayor Bottoms intends to modify the zoning code with some or all of these changes. That would require approval from the city counsel, and hopefully a lot of input from our citizens.