Peachtree Road United Methodist Church aims to demolish a historic Buckhead Forest house for a new parsonage, stirring preservationist concerns.

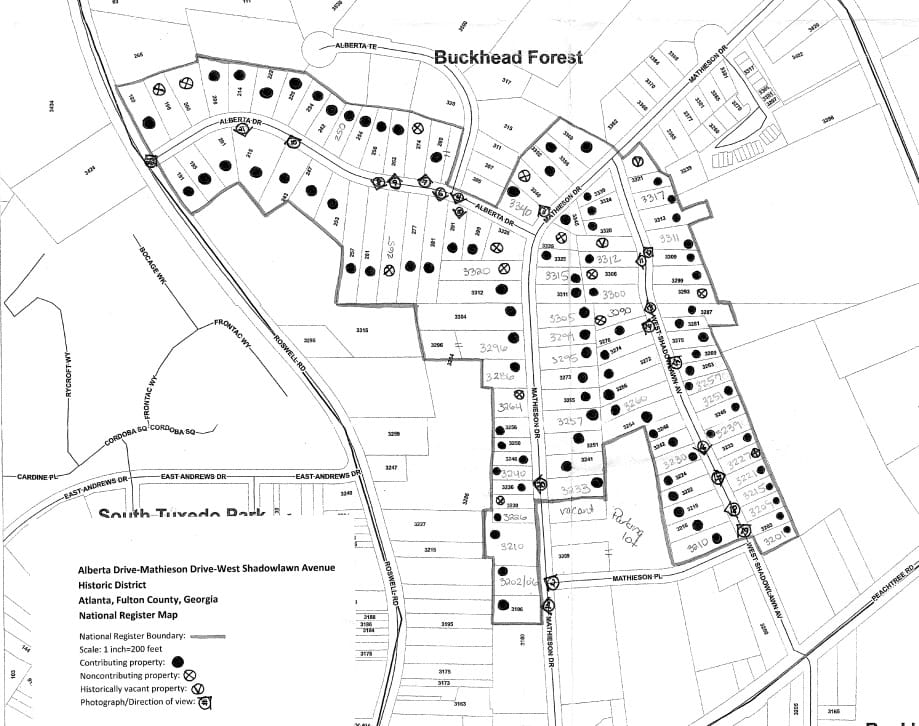

The 81-year-old house at 3210 West Shadowlawn Ave. is listed as contributing to the Alberta Drive-Mathieson Drive-West Shadowlawn Avenue Historic District, which was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2015. But that does not prevent demolition and the property has no City historic protections. The church claims the house is “uninhabitable” and can’t meet its mother organization’s requirements for large parsonages.

David Yoakley Mitchell, executive director of the nonprofit Atlanta Preservation Center (APC), said that “this symbolic community continues to be threatened” since the historic district’s creation, with the demolition plan as the latest example.

Economic interests and development time pressures can provide “an umbrella to remove these cultural contributions to our city with little concern,” said Mitchell. “Yet, until the residents of these communities, these neighborhoods, and this city start to embrace the valuable story that is told visually through our buildings, structures and spaces, we will continue to place an assessment on identity that will arguably be difficult to sustain.”

The nearly century-old church has been at its present location at 3180 Peachtree Road since 1941, the same year the West Shadowlawn house was built. Over the decades, the church has acquired several surrounding properties. Those include two other West Shadowlawn houses also listed as contributing to the historic district: Numbers 3201 and 3218.

In recent years, the church demolished the house at 3201 and replaced it with a new parsonage for one of its staff clergy. It appears that demolition passed with no official or media notice that it involved a historically significant property.

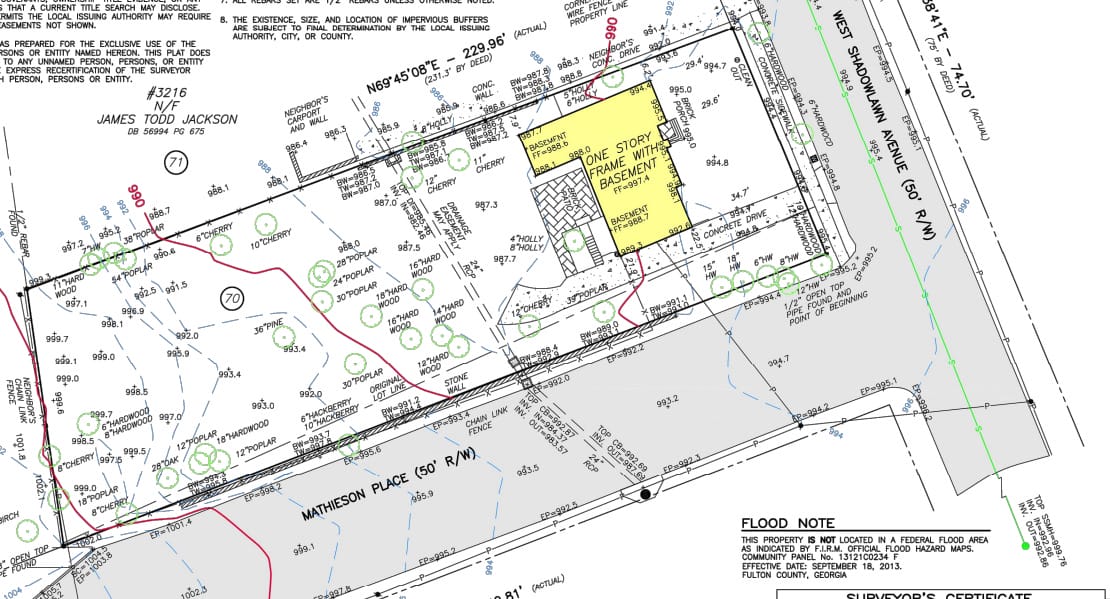

Now the church has the same plan for 3210 West Shadowlawn, at the intersection with Mathieson Place, which it bought in 2018. The property sits within Special Public Interest District 9 (SPI-9), a specialized zoning district whose Development Review Committee (DRC) heard the plan at a Sept. 7 meeting. The proposal stalled until at least November over a sidewalk issue unrelated to the historic status.

The DRC’s purview does not include historic preservation and the issue was raised only by Mitchell as a visitor to the meeting. However, he was not aware at the time of the property’s status as contributing to a historic district and no one from the church mentioned it. Buckhead.com discovered that status through research after the meeting. Sellers could not immediately be reached for comment.

The historic district application was filed with the National Park Service in 2014 by the Georgia Historic Preservation Division. The filing says the neighborhoods are historically significant as part of a building boom that followed a 1907 trolley line extension on Peachtree, and for its wealth of intact architecture dating from the 1910s through the 1960s. West Shadowlawn, the filing says, was named for a subdivision called Shadow Lawn, which started construction in 1922. The filing includes a photo of the house at 3210. The main church property is not included in the historic district.

Rev. Bill Britt, the church’s senior minister, told the DRC that the plan is to build a parsonage as a home for a member of its clergy who currently rents elsewhere in the city. The existing one-story house would be replaced with a larger, two-story version.

Mitchell urged the church to consider preservation possibilities.

Project architect Brandon Ingram noted that many houses on the street date to the period of the 1920s through 1940s. He said the church wanted the new parsonage to be be “respectful” of that aesthetic and look “a little bit more vintage” rather than “some giant Buckhead McMansion.”

Mitchell asked why they didn’t retain that aesthetic by saving the house, and suggested that the existing structure might be “more in line with the humility” of the clergy profession. He also greeted Sellers, noting he knows her from her previous service as chair of the Atlanta Urban Design Commission, a City body that reviews demolitions or other changes to historic properties with legal protections or City ownership.

However, Britt and project attorney Julie Sellers, who is also a church member, claimed the house can’t be saved. “It’s really in uninhabitable shape,” claimed Britt, while Sellers said it looks better on the outside than on the inside.

Britt added that the church’s trustees “spent a good bit of time talking about preserving it, remodeling it – what it would take.” Another alternative, he said, was turning the 3218 West Shadowlawn site into the new parsonage and renting out 3210. But the final analysis was that demolishing and rebuilding at 3210 was the most cost-effective approach.

He said another issue is the mother United Methodist Church’s (UMC) requirements for parsonages, which include a minimum of three bedrooms, two-and-a-half bathrooms and a covered garage. (The website of the UMC’s North Georgia Conference posts slightly different standards: at least four bedrooms and two bathrooms.)

As for the possibility of salvaging some materials and incorporating them into the new parsonage, Ingram said, “l’d absolutely love to use what we could.” But, he added, the house is not a “spectacular example” of architecture and lacks “super-fine details.”

Mitchell said he is not an “absolutist” on preservation and that there are always discussions to be had on preservation methods. He offered to visit the house to affirm the claims of its condition and possibilities, which the church representatives did not immediately take up.

Mitchell said he had not heard from the public specifically about this house, but that he’s getting more calls about the loss of these sorts of things” and wanted to bring attention to it.

The project ended up stalling until at least November due to a sidewalk issue.

Sellers initially said she believed no zoning variations would be required. But then the DRC and City planner Alex Deus reminded her that SPI-9 and other zoning includes streetscape standards that likely would require new 6-foot-wide sidewalks and a 4-foot-wide planting strip along both street frontages.

The DRC was inclined to recommend a variation for the West Shadowlawn frontage to keep an existing, smaller sidewalk so it doesn’t clash with the rest of the street. But the DRC wanted more study of adding a sidewalk on Mathieson Place, especially after hearing it is heavily used for church services and activities. However, that may have challenges with tree removal, a retaining wall and a storm sewer that runs through the property.

Sellers said that the variation request adjustment would mean that the church could not seek a special administrative permit, required within SPI-9, until November anyway. So that gives it time to study sidewalk possibilities. Now it may also face more pressure about preservation. The project has yet to be formally presented to local neighborhood organizations, the church team said.

After the meeting, Sellers could not immediately clarify how the church currently uses its third house on the street, 3218 West Shadowlawn, and what the future plans may be. That historic district-contributing property dates to 1940, according to Fulton County property records.

Redevelopment on West Shadowlawn and its sibling street on the other side of Peachtree, East Shadowlawn, are showing some patterns that raise broader issues of historic preservation and the limits of the SPI-9 standards.

East Shadowlawn also is lined with houses from the same period, many of them converted to business use. A new trend there is demolishing the historic house and replacing it with a similar house-like structure for commercial use. That raises the possibility of rehabilitation and reuse instead, but those conversations have not happened, as there is no historic district and the DRC’s purview does not include preservation. However, the DRC also often raises environmental efficiency issues, and historic preservation is increasingly pitched nationally as such an issue, because reusing a building takes less energy and waste than demolition and new construction.

In addition, both are small-scale residential streets, while SPI-9’s standards focus on more large-scale, urban-style projects with such requirements as wide sidewalks and significant amounts of ground-level windows. The DRC has repeatedly recommended variations from those standards on East Shadowlawn, as it is poised to do for this West Shadowlawn project.

Asked after the meeting about those broader issues on these types of streets, DRC chair Denise Starling said she understands historic preservation can get “pretty tricky,” but that more environmental standards could be a plus for both SPI-9 and its adjacent Special Public Interest District 12.

“We are probably getting to a point where we need to do a quick update to the SPIs with a green focus in general,” she said.