What a difference a year makes in City rezoning.

In late 2021, Buckhead was an epicenter of fury about proposed zoning and land-use changes aimed at boosting density and affordability in some single-family neighborhoods.

By late 2022, a course correction under a new mayor and City Planning director had Buckhead’s District 8 City Councilmember Mary Norwood so pleased, she’s proposing Tuxedo Park as a test case for one of the new zoning code concepts – one that would keep density low.

“I am a big proponent of the process and the intent [and the] vision so far,” said Norwood.

Atlanta’s zoning code hasn’t been fully updated since 1982, a problem the City has inched toward fixing for years. A preliminary step was revising the Community Development Plan (CDP), a planning policy document upon which zoning code is typically based. Dramatic and complicated changes to the draft CDP – including ones aimed at allowing more density in single-family neighborhoods – last year drew complaints from Buckhead’s Neighborhood Planning Units (NPUs) and criticism from a state regulatory agency.

Meanwhile, the Department of City Planning (DCP) was proposing several highly controversial zoning code changes also aimed at density, particularly allowing accessory dwelling units (ADUs) in more single-family neighborhoods. Proposed under former Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms and former City Planning Commissioner Tim Keane, the legislation aimed to address historic, racism-based inequity and increase affordability. But their issuance in a nontransparent and confusing fashion fed even more controversy in many neighborhoods and particularly helped to fuel the Buckhead cityhood movement.

Amid outcry, the City stepped back from such proposals and approved a reduced version of the CDP — known as “Plan A” — due to a state legal requirement for an update every five years. The City promised more public input into a full CDP revision, which is currently projected to wrap up in 2025.

Meanwhile, Bottoms and Keane have left. Mayor Andre Dickens has been far more sensitive to neighborhood concerns and new Planning Commissioner Jahnee Prince is leading a department that is going slow on the CDP and instead focusing on a rewrite of the zoning code dubbed “ATL Zoning 2.0.”

Led by the urban planning consulting firm TSW, that zoning rewrite is in the midst of a public workshop phase. TSW’s Caleb Racicot said at a Nov. 29 workshop that “we’ve got to take this at the speed of trust” to ensure neighborhood input.

Revisions of CDPs and zoning code are typically done more or less simultaneously, but the CDP often is finished first, as code follows policy. The City is doing the reverse this time, specifically saving any major changes to zoning districts for the CDP rather than code. That’s clearly to delay the political heat and focus on relatively dry zoning code. Racicot said the rationale for not changing the districts in the code is “how passionate people can get about zoning changes on one particular property,” especially if it’s “changing density and use.”

Norwood says that “when you’ve got two-thirds of the NPUs unhappy with the CDP,” it makes sense to start with the code instead.

However, the code ideas being floated would empower some of those controversial changes. Implicitly referring to density debates, Racicot said that some neighborhoods want change and others don’t. So TSW is proposing a new approach to district designations that would allow nuanced and localized options without changing the overall zoning.

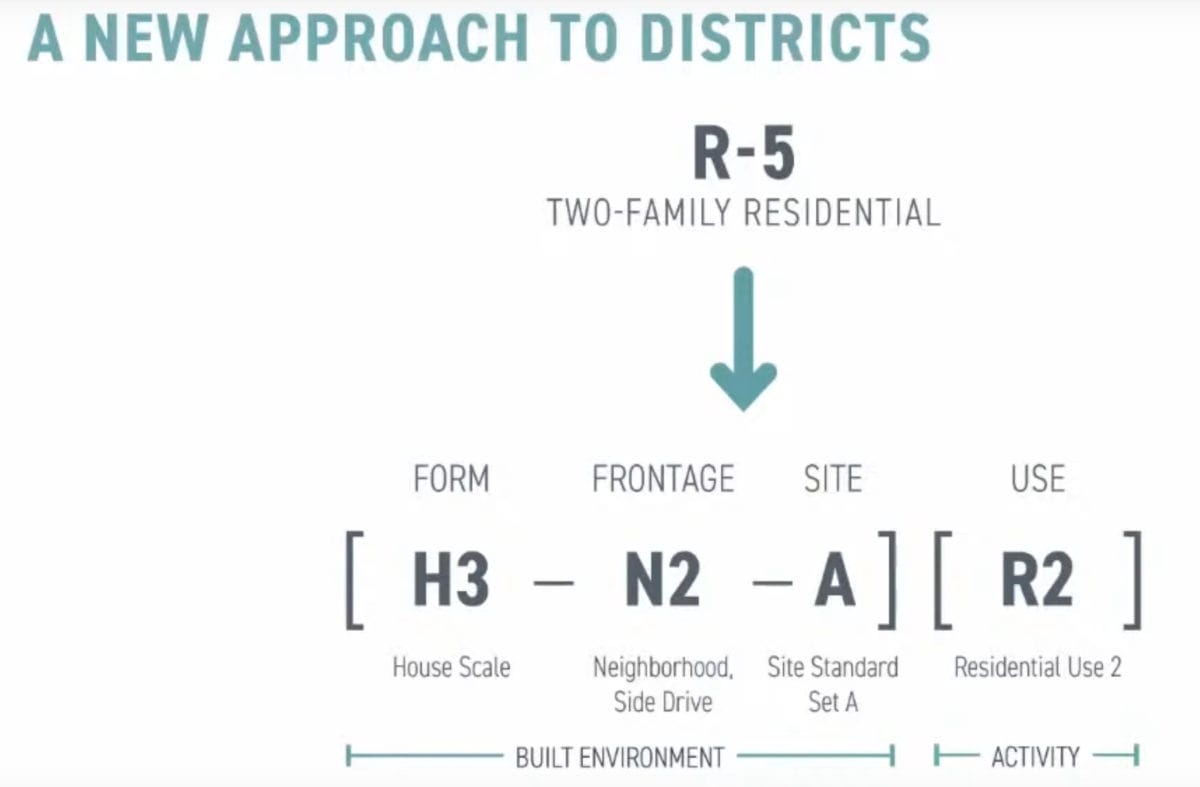

The idea is “zoning strings.” Current code designates districts by names that indicate the type of use that’s allowed, such as R-5 for a residential category, but in the body of the text also restrict other main features of zoning: form, frontage and site characteristics. The zoning strings concept is to keep all of those four elements separately named and controlled, so each can be changed like dials on an instrument panel to get more nuanced results. An example planners showed at the Nov. 29 workshop was “H3-N2-A R2,” where the designations refer to the form of a house, its frontage on a side street, the site development standard, and the residential use. Any of those individual designations in the string could be changed while leaving the rest.

It’s a newfangled idea, but also an old one – Racicot said Atlanta had a version in its 1920s code. (Incidentally, that’s the code whose explicit racism and its lingering effects on segregation and inequity is what Bottoms and Keane were trying to undo with some of the controversial zoning proposals.)

Racicot asked the public to suggest areas where planners could test some of the zoning concepts in pilot projects before they finish their work. That got Norwood’s attention. She thinks the zoning strings format is a way to tackle an issue that has bedeviled Tuxedo Park: subdivisions that change historic lot dimensions and patterns. She has submitted a City Council paper that would establish a zoning string format in the neighborhood under the existing concept of an overlay called a Special Public Interest (SPI) district. The site and frontage parts of the string would fine-tune the lot dimensions to avoid subdivisions.

“It is essentially a demonstration project, a pilot project, that will show the appropriate interpretation of what they have called a zoning string,” said Norwood. “… So we stepped up to the plate and they are on board.”

“I have liked what I have seen, and I am very grateful that the planning department saw this one ordinance – very simple, one page, one paragraph – that addresses an issue of concern to the specific neighborhood and there is a way that I can do this,” she continued. “Thirty years ago, it was either you had to be a historic district with all these regulations or there was nothing for you. So we have come a long way from that point of time in the city to where I can use an SPI for this one issue.”

It remains to be seen how that works out and what the public at large thinks of code proposals as the rewrite heads toward a final version expected in summer or fall of 2024. The process already ran into a snag with complaints about a survey that included highly technical language. However, there are many more opportunities for input, including three major workshop meetings continuing into April 2023. For full details, see the Zoning 2.0 website.