Nearly eight years have passed since an incurable killer of a beloved garden plant was first found in Georgia, lurking in a Buckhead lawn. Now boxwood blight has spread to devastate historic gardens and local landscapes across the country, while science is starting to catch up to the tricks of the fungal infection behind it.

Chris Hastings, owner of the Chamblee-based tree care firm Arbormedics, has been battling the blight in Buckhead gardens from Day One. He summed up the current state of affairs: “Is it bad? Yes. Has it gotten worse? Yes. Is it now commonplace on almost every street in Buckhead? Yes.”

However, Hastings adds, it also has not wiped out the plants as was originally feared. “But over all that time… it comes in waves,” he says, noting a particular blight-battling hint in its link to rainfall and moisture. “And really we’re still trying to figure out, what are those key moments? Because it’s not always as clear as you would expect.”

“The boxwood is such a beloved plant. It’s the aristocrat of the Southern garden.”

Chris Hastings, owner, Arbormedics

Jean Williams-Woodward is a University of Georgia Extension plant pathologist who was on the team that first identified the blight on boxwoods on that Buckhead property back in 2014. She says that “we’re still finding out things about this disease.”

The future she sees taking shape — much like the famously sculpture-friendly boxwood itself — is one where improved practices, disease-resistant breeds and a shift to other types of landscape plants will contain the blight.

Boxwood (Buxus sempervirens) is a type of small-leafed, evergreen plant native to Asia that for centuries has been popular nearly worldwide as an ornamental. In tree form, it makes for stately, pillar-like entrance ornaments. It also takes well to being shaped with trimmers and is hugely popular for rectangular hedges — which is how the plant got the “box” name. The English and American varieties are wildly popular cornerstones of the traditional Southern aristocratic garden.

“In the South… it’s a plant that tugs on your heart,” says Williams-Woodward. And on your purse-strings, too — for nurseries and landscapers, “It’s a huge economic impact.”

“The boxwood is such a beloved plant. It’s the aristocrat of the Southern garden,” said Hastings, adding that’s why homeowners are willing to battle the blight instead of just getting replacement plants. “It’s been used for hundreds of years here. It’s been tied in people’s minds and their sensibilities to what a gorgeous Southern garden looks like. So it’s very hard to contemplate having a holly instead.”

The blight arrives

This pretty picture started going bad with the original discovery of boxwood blight in the United Kingdom in the 1990s. An American infection was just a matter of time, and in 2011, the first U.S. cases were found in Connecticut and North Carolina nurseries. A Virginia nursery was the likely source of infected plants that led to that first known Georgia case in Buckhead in July 2014, on a private property that the experts won’t publicly identify for privacy reasons. The blight may well have been elsewhere in Georgia already.

The blight has continued to spread around the country and has become a major pest in historic gardens. Colonial Williamsburg, the famous historic area in Virginia, has been battling the blight for over five years in its collection of more than 8,000 boxwoods, many dating back a century or more, according to media reports. In the past year, major boxwood culling was carried out at the historic homes of poet and author Carl Sandburg in North Carolina and 19th-century politician Henry Clay in Kentucky.

“I’ve seen very historic gardens where every single plant has been lost… They just look like bare stems,” said Williams-Woodward.

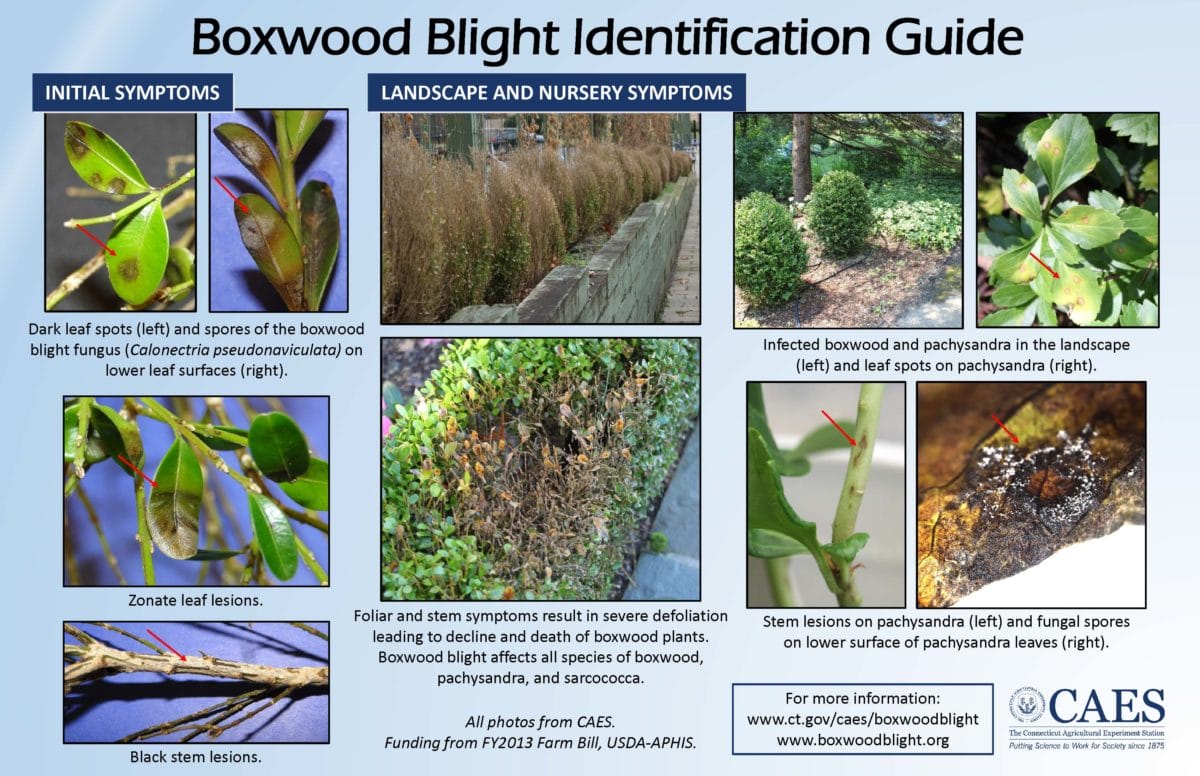

The blight is a species from a genus of plant-infecting fungi. It kills boxwoods by causing their leaves to die, and can infect the stems as well. The blight can also infect other plants in the same family, including pachysandra and sweet box, according to Williams-Woodward, but is often not so lethal to those species. Some varieties of boxwoods have a degree of resistance, but the beloved dwarf English and American cultivars are not among them.

The fungus spreads by sticky spores that spew off the plant into the environment. Once it infects a plant, there is no known cure.

Williams-Woodward says the fungus has probably been around for hundreds of years, but was less prone to kill boxwoods in their original native areas of today’s Asia and Turkey, where the climate is drier. Wetter conditions are among the factors that make the fungus thrive.

New research, new tactics

In the first decade of battling the U.S. blight, tactics have shifted along with research and field practice, and even now there is some disagreement among experts about how the fungus spreads and should be fought.

Hastings notes that the early U.S. discoveries were inside mid-Atlantic nurseries and greenhouses, with plants packed closely together. That led to some assumptions about how transmissible the fungus was and that the air might be a major transmission method for its spores.

“So I do think there was a little bit of a misunderstanding in the early days about how contagious it, how lethal it is,” said Hastings. “So a lot of the original reports that came out and still linger were like, ‘If you have boxwood blight on your property, tear them all up and run screaming for the hills.'”

Yet today, he says, some original boxwoods continue to survive on the original Buckhead property that was the first known to have the blight. He said a second Buckhead property where the blight was found in backyard plants at virtually the same time still has boxwoods, too, including some within 100 feet of those with the outbreak.

What everyone agrees on at the moment is that moisture is key to the blight’s spread and that the disease can be managed with multi-pronged tactics. The situation can be illustrated with imperfect analogies to more familiar human diseases. Think of the blight as a lethal version of athlete’s foot that, like that fungus, infects and spreads explosively in wet environments. And like the coronavirus behind COVID-19, experts can’t currently cure or eliminate the blight, but can contain and manage the disease through a combination of treatment, built-up resistances, avoidance and new, safer cultural practices.

The blight erupts when the weather is wet and temperatures are moderate, said Williams-Woodward. The symptoms may retreat in hotter and drier months, she said, giving plant-owners a false sense of relief while the incurable infection remains.

Water is also now believed to be one major way the fungus spreads, as splash-back from rain or irrigation droplets hits other nearby plants. “Spores produced [by the fungus] are very sticky and they cluster together,” said Williams-Woodward. “So this pathogen or disease is not something that blows around in the wind. It’s mostly water-splashed.”

Hastings agrees that water is a major factor, saying that the earlier wind-spreading explanation never matched what he saw in the field. “We do not see it marching through a garden,” he said, explaining that the blight is almost always paired with heavy moisture from the environment. He said he often finds it tied to a broken rain gutter or — especially in lawns of well-to-do Buckhead homeowners — irrigation systems that are overused when rainfall is perfectly adequate.

“Irrigation, irrigation, irrigation is the number one reason that people have [boxwood blight] problems in Buckhead,” he said. He won’t even take on a boxwood client who won’t properly manage an irrigation system.

“I think we will end up in some kind of combination of planting less-susceptible varieties, plus some cultural practices … So we can manage this disease.”

Jean Williams-Woodward, University of Georgia Extension plant pathologist

Research shows that animals and humans may also be carriers of the spores, says Williams-Woodward. Boxwoods “actually smell like cat pee,” she said, and so may attract cats and dogs to mark them, resulting in spores getting on their fur to be spread to other plants. She said she saw one garden where boxwoods were blighted at the same level as the cushion on a patio chair that a cat slept on. Squirrels, rabbits and turkeys are other suspected spreaders.

Landscape workers may also spread the spores on their hands and equipment, Williams-Woodward said. She is currently conducting experiments on easy ways for landscapers to disinfect their gear before traveling to another property. Regular Lysol spray is looking highly effective, she said.

Hastings doesn’t buy it. He says animals and humans pale in comparison to water and another form of Buckhead lawn epidemic — the use of high-powered leaf-blowers that could blast spores all over surrounding properties. “I don’t think we need to be caging our cats and spraying down our landscapers,” he said.

Sprays and resistant varieties

What about spraying the plants themselves? After all, you can knock out athlete’s foot pretty fast with a can of fungicide from the drug store. Turns out it’s not that simple for boxwood blight, and Hastings and Williams-Woodward agree it’s no main solution.

There are fungicide sprays that can effectively reduce blight symptoms in a plant, said Williams-Woodward. But it requires regularly repeated application that few landscapers or arborists will perform, and that can be cost-prohibitive and raises issues of environmental pollution. Overuse of the sprays also could lead to the evolution of fungicide-resistance strains of the blight, she said.

Hastings said he’s one of the few local arborists who will spray for boxwood blight, but only as part of an integrated approach, as he also has environmental and best-practices concerns.

“Do we put every boxwood in town on a chemical crutch? Absolutely not,” he said, again emphasizing moisture as the main problem. “The key to getting ahead of this is thinking about your basement getting mold or mildew… You don’t run in there and start spraying Clorox everywhere. … You get rid of the water source.”

Another option is blight-resistant varieties of boxwood. Some already exist and others are being cultivated. But a note of caution on some of those, such as Japanese and Korean varieties: Williams-Woodward said they may be less able to catch and die from the blight, but can still carry and spread it, making them “sort of a Trojan horse.”

Her preferred tactic is to simply replace smaller boxwoods with a totally different species, like Japanese holly, and to prune the lower branches of larger ones to avoid the water-splash effect that may spread the spores.

Hastings says he’s hopeful the boxwood blight battle eventually will take a similar course as brown patch, a different fungal infection that affects fescue grass lawns. He said that landscaping veterans have told him about the brown patch plague in the 1980s, which coincided with a boom in lawn irrigation systems. Initially, he says, there was similar advice to landscapers about attempting to disinfect mower blades and the like. Today, he said, brown patch is manageable in a coordinated program of lawn management techniques that continues to allow fescue to be planted.

Williams-Woodward also looks to a future of containment and management. She said research continues on exactly how the blight spreads, the environmental conditions that favor it, how its biology works, and arborist techniques. “I think we will end up in some kind of combination of planting less-susceptible varieties, plus some cultural practices … So we can manage this disease,” she said.

For more details about boxwood blight, see the websites of the UGA Extension and the Georgia Department of Agriculture.