Most folks in Buckhead know there are horses stabled in Chastain Park. But even many locals don’t know the true humanitarian mission of Chastain Horse Park.

Created over 75 years ago as stables and riding grounds for wealthy horse owners, CHP now is an accredited center for “equine therapy” where people get help with physical, cognitive and emotional issues by bonding with the animals and other riders. And this week, it began work on a two-year, $8.9 million campus renovation to upgrade and expand such programs.

“The magic that happens here with our horses is incredible,” says CHP Executive Director Trish Gross, who led Buckhead.com on a facility tour shortly before work began.

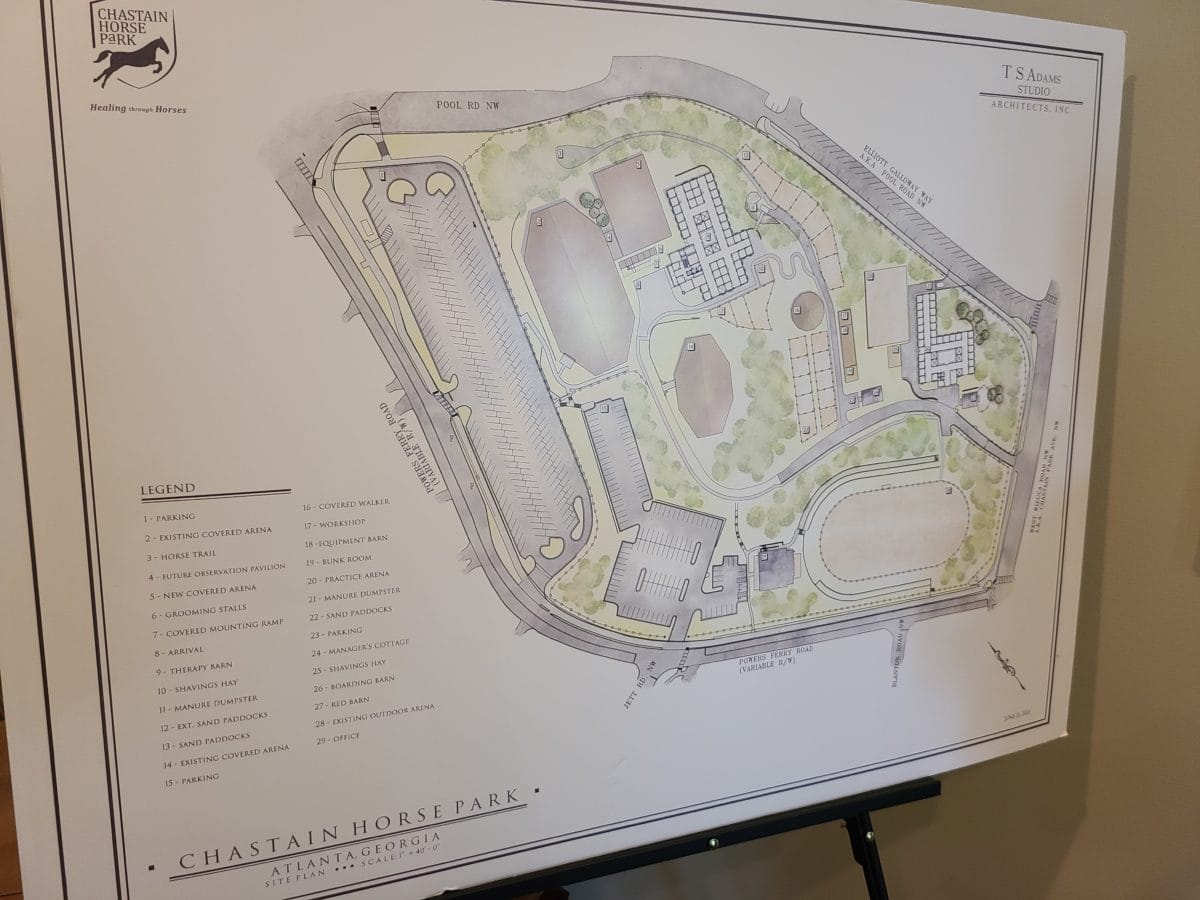

CHP occupies about 15 acres of the City park at Chastain Park Avenue and Powers Ferry Road. It’s a private nonprofit that holds a long-term lease from the City that includes the right – and the responsibility – to build and pay for just about everything that happens there, contingent on continuing to offer therapy programs.

Back when the green space opened in 1945 as North Fulton Park, Buckhead was a rural area not yet part of the City of Atlanta, and many people had horses. The park included horse facilities, including a covered arena whose stone walls – likely built by workers in President Franklin Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration programs – still stand today.

CHP still offers horse boarding, which is an important revenue stream, but that’s not its main function. Ditto for a large clubhouse known to the public as a place to host events. And while it stands within a public park, the private CHP is not a kind of horse zoo that anyone is free to wander. In fact, CHP has become what Gross calls “unfortunately, a best-kept secret” of the neighborhood.

Its true mission is the therapeutic programming, which serves hundreds of people each year thanks to a staff of 15 and many more volunteers. Those programs started so small sometime in the 1970s or ’80s, Gross says, that no one is really sure of their history. The formation of CHP as a formal nonprofit in 1999 was the beginning of a serious, nationally accredited program. In 2005, a team of physical and occupational therapists called My Heroes began working there, and in 2011 launched a second equine therapy program at Colorado State University.

The programs help people with a wide variety of challenges, such as cerebral palsy and autism. And a new psychotherapy pilot program will begin this fall. CHP has facilities and equipment specialized for therapy, such as a lift to help people who use wheelchairs to get onto a horse, and a “Sensory Trail” with various sensory engagement devices on posts or trees at horseback height. There’s also “Elvis,” a mechanical horse used to give therapy clients a taste of riding before trying the real thing.

“One of the tools that I use is the movement of the horse,” said CHP physical therapist Michelle Winer, explaining the motions can be soothing while also increasing a rider’s core muscle strength.

Most of the clients are youths, but about a quarter are adults. And they come from all over – with regulars hailing from as far as Macon – and across income groups. CHP subsidizes half of the programs and offers full and partial scholarships for those in need.

“It’s not 30327 serving 30327,” said Gross, referring to the swanky local ZIP code. “We’re 30327 making a difference for all of Atlanta.”

CHP also offers field trips for school students and at-risk youths, and a summer camp program that remains on pandemic hold but may return for 2023.

CHP owns the horses used in the therapy programs, which are selected for their temperament. Many of the horses are pets donated by individuals – including Gross herself, whose horse Dawson became part of the team in 2017. Combined with the privately boarded horses – many of them show horses – the total equine population any given day is around 50 to 60.

While these programs have boomed, the facilities have not. Most of the barns and paddocks date to the 1990s, when the nonprofit was formed, and are now inadequate and facing maintenance issues. Many even lack heating and air conditioning. And staff and volunteers work not only in the barns, but literally within stalls meant for horses.

“Our volunteer lounge is a stall,” said Gross. “The same stall is our kitchenette. The same stall is our volunteer coordination office.”

During the recent visit, a volunteer training was being held in the aisle of a barn, with a screen erected against the barred doors. Given the high-level accreditation and amount of programs, Gross said, the facilities are “subpar for what we do.”

Hence the “Healing Through Horses” capital campaign that, despite the pandemic, has raised most of the money needed to begin building new facilities. Demolition on one barn was scheduled to begin this week, with similar demolitions and reconstructions cycling over the next two years as programs and horses are shuttled between them. The main facility, the Therapeutic Horsemanship Center, will include stalls for 40 offices and many facilities for humans.

New paddocks are coming as well, while some facilities, such as the main arena and clubhouse, will remain untouched. There also will be housing for the on-site manager, Lori Barefoot, who currently lives in an apartment over one of the barns.

Some trees are coming down, Gross said, and will be replaced with new plants per City code. Part of the tree removal is required for an upgraded stormwater detention pond.

The end result will be modernized and somewhat larger facilities to handle an expansion of programs, though Gross says the number of horses should remain about the same. The plan includes a barn with stalls for 40 horses. Likening the project to a hotel, Gross said CHP is not going the cheap route but also not building something too fancy.

“We are going mid-level Marriott, not St. Regis or Motel 6,” she said.

It’s still a massive undertaking for a relatively small nonprofit. CHP still needs to raise about $900,000 to finish off the work. That’s on top of roughly $775,000 a year it needs to raise to maintain its $2 million operating budget. The next big annual fundraiser is coming in October.

A high-energy former tech business founder from the West Coast, Gross is used to raising money in the hard-bitten word of venture capital.

“This is whole different kind of investment,” Gross said of CHP fundraising. “When I’m raising money, I’m asking for an investment… in our community, in our integrity, in ourselves, in our humanity.”

Gross moved to the Chastain Park neighborhood in 2015 when her husband, a Cox executive, relocated to Atlanta. A horse-lover herself, she fell into CHP and eventually its leadership role. She is set on spreading better public understanding of its mission and the camaraderie that develops among clients, volunteers and horses.

“We’re a community. It’s a community focused around horses,” said Gross. And for those in it, whatever the stresses and changes in other parts of their life, “Everybody comes to the barn.”

For more about CHP and its capital campaign, see chastainhorsepark.org.