“I know most of you think that it’s 9 in the morning, but actually we have been transported back in time to July 22nd, 1864 at about 4:30 in the afternoon,” Jessi Gordo explains to the crowd who have gathered on a foggy Thursday morning at the Atlanta History Center. The large, round room is dark and visitors peer eagerly over the edge of the platform towards the diorama and painting beyond.

A 12 minute video is cued up and projected onto the Cyclorama itself that explains the story of the painting’s creation and evolution throughout the years. This is the public’s first chance to view the Cyclorama in its new home at the Lloyd and Mary Ann Whitaker Cyclorama Building. The $35 million campaign to restore and move the Cyclorama has been well invested. While Atlantans might remember this work as merely a painting, the Atlanta History Center has transformed the exhibit into an immersive, modern experience that is sure to become a destination for visitors and locals alike.

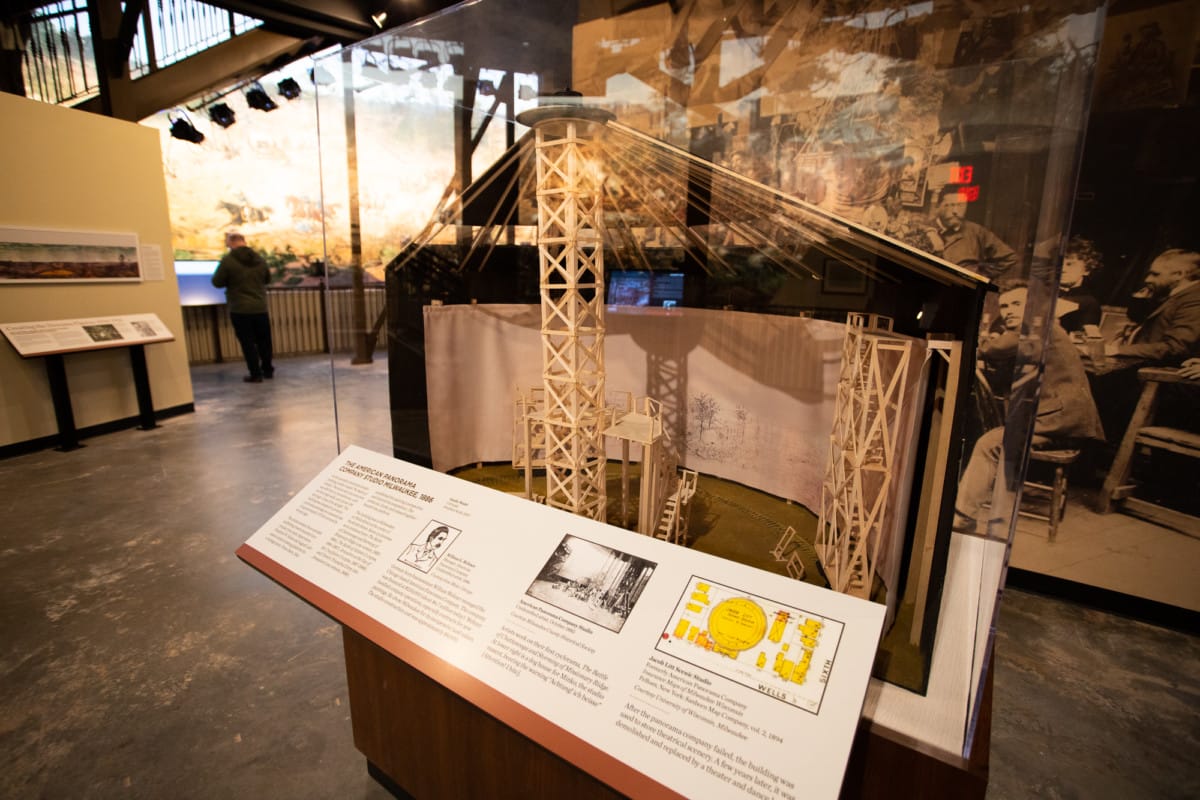

Originally hand-painted by 17 German artists in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, the Cyclorama is a 132-year-old painting and diorama that depicts the Battle of Atlanta, a fierce skirmish that ultimately decided the Civil War in the favor of Union soldiers. The panoramic painting, weighing in at 10,000 pounds, is 49 feet tall and longer than a football field. It’s one of only two surviving cycloramas in the United States, and at the time of its debut in

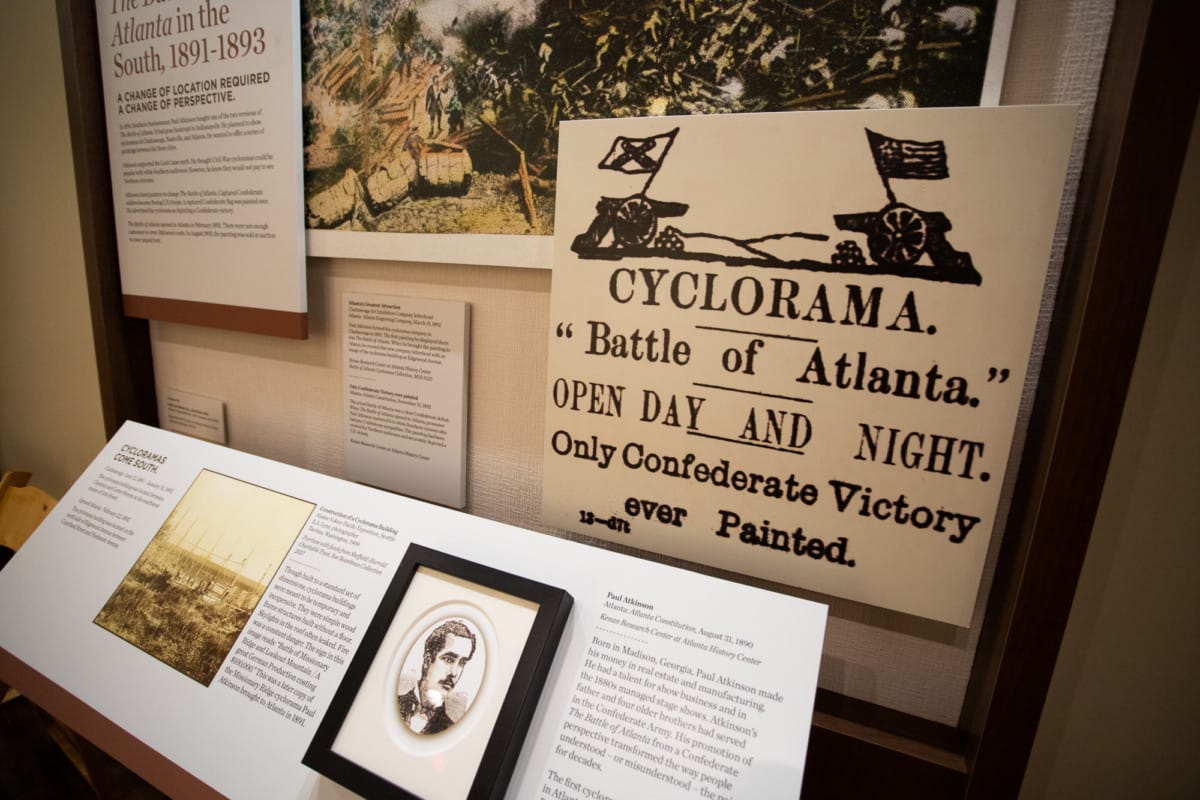

While the Battle of Atlanta certainly carries both historical and personal significance for residents in the area, the painting itself has evolved into an artifact of its own right. Throughout the years the painting has moved from place to place and has been interpreted in different lights. When Paul Atkinson purchased the painting an an auction in 1890 for a price of $2500, he decided to move the display south and installed it in Chattanooga. Knowing that southern audiences would take offense to the depiction of the Confederate loss he chose to make a few modifications which included removing a disgraced Confederate flag, changing fleeing Confederate soldiers to resemble Union soldiers, and decreeing the image of two unknown soldiers as a pair of brothers that fought against one another before reuniting on the battlefield.

“He sees this as an opportunity to tell a story,” explained Gordo. “He knows that if he can connect an audience with the painting, that he’s got them. Because that’s free marketing – that’s the best way to get you in the feels and get you connected to it.” A newspaper billed the painting as the “only Confederate victory ever painted,” and it was displayed in a wooden building on Edgewood Avenue until it proved a financial failure and the roof of the building caved in. Ernest Woodruff bought the painting in August of 1893 and quickly resold it to George V. Gress and Charles Northen, pulling a small profit.

Gress and Northen set about repairing the painting and removing the inaccurate changes that Atkinson had implemented before moving it to a wooden structure in Grant Park, but competition with new nickelodeon theaters caused the business to falter. In March of 1898 Gress donated the painting to the city of Atlanta, and in October 1921 it was moved to a “fireproof” building in Grant Park where it lived for the next nine decades.

Over time and with each major move, the painting underwent trimming of the sky achieved by folding down the top edge and the removal of vertical slices in order to fit in the various buildings where it was displayed.

In the 1930s the diorama was added by the Works Progress Administration (WPA) which features 128 plaster figures and includes a cameo by actor Clark Gable of “Gone With the Wind,” who is famously said to have claimed “the only thing that would make this better is if I was in it.” The city acquiesced to this request, and visitors can view the somewhat distressing depiction of Gable as a fallen soldier lying prostrate on the red Georgia clay.

Deteriorating conditions of the Cyclorama came to the forefront in the 60s and 70s as the city considered other, more suitable homes for this impressive artifact. Cost considerations ultimately prohibited the painting from being removed and it was treated by a conservation team in its Grant Park home. The $11 million

In 2014 Mayor Kasim Reed signed a license decreeing the Atlanta History Center as the Cyclorama’s new residence for the next 75 years. Moving the massive, delicate painting from Grant Park to Buckhead was a monumental undertaking. The painting was meticulously rolled up onto two 45-foot-tall spindles and moved to the Atlanta History Center by crane in 2017. In the last two years, the Atlanta History Center staff and a crew of talented art restoration experts got to work cleaning up and repairing the painting, restoring sections that had been removed and ensuring that the new display setup would not sag or damage this historic piece of art.

Joseph Lazzari, one of the local artists who helped to restore the Cyclorama painting itself and corresponding diorama for the move to the Atlanta History Center, said the work was challenging but enjoyable. Using modern oil paints to recreate and blend the image with the existing 132-year-old artwork took precision and patience. Moving and working around the 3D figures, which are fragile plaster over steel armatures and thus very heavy, was difficult. “Re-sculpting, repainting, and bringing them back to life was the easy part – and it was really rewarding work,” said Lazzari.

“Honestly every single day that I worked on this project, no matter how difficult, was my favorite day,” Lazzari continued. “I can’t begin to express how fortunate I’ve felt to be a part of this project. I was a kid who dreamed of being an artist and I’ve spent most of the last year contributing to a 140 year old conversation that lives in this piece of art.”

“It’s the coolest thing I’ve ever done.”

In the wake of intense debate over Confederate monuments in the United States, the city’s commitment to display the Cyclorama has garnered a variety of reactions from viewers. “I think people are going to be surprised,” said Sheffield Hale, President and CEO of the Atlanta History Center, “to find out it was a painting painted in the North to celebrate a Northern victory for a Northern audience. But the really interesting, cool, and important thing about the painting is that it came South and took on the Lost Cause ideology.”

Though the painting has been viewed from a variety of standpoints and with a number of different interpretations, the depiction of the Battle of Atlanta is an important reminder to all of us of the war and skirmishes of the Civil War that once set our great city aflame. “That is what makes this such an incredibly important icon – or artifact – to show how the location, time, and place can change people’s perspective and spin they put on history,” Hale continued. “It’s about the use and misuse of history and historical memory in a very tangible way.”